Shot in the Lowcountry, this piece shows how Charleston's Ranky Tanky pulls Gullah play songs and spiritual textures into a contemporary bandstand. It's secular stagecraft with sacred muscle memory.

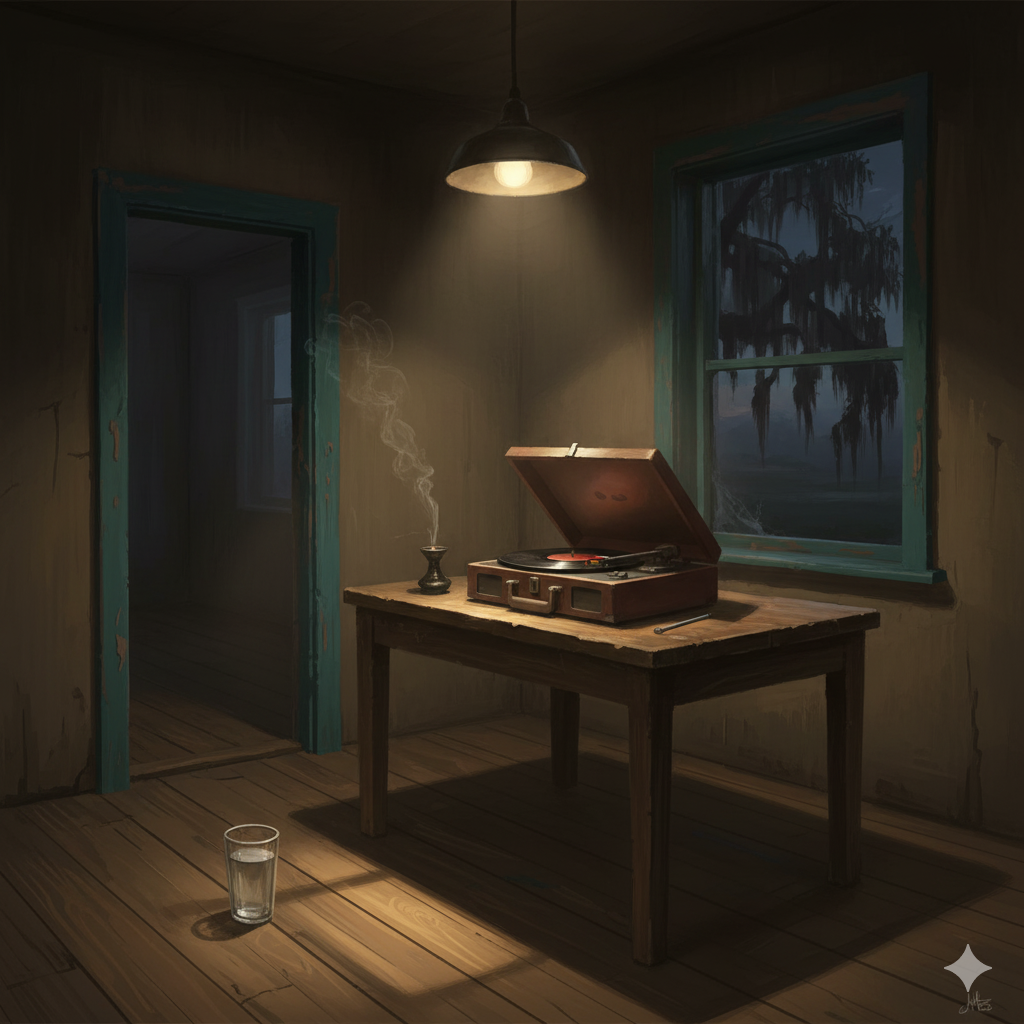

The line between the altar and the juke has always been thinner than outsiders think. In the Lowcountry, rhythms and words move back and forth—ring shout steps showing up in a Saturday groove, a Sunday voice slipping into a Friday night lyric about roots, mojos, and keeping harm at bay. That's not contradiction; that's our toolkit. "Conjure Music" is where I gather performances and essays that make that traffic visible: the McIntosh County Shouters carrying the shout into the present, Ranky Tanky turning children's rhymes and praise fragments into jazz-layered joy, scholars tracing how hoodoo language walks through blues and R&B. This is secular music doing sacred work—holding the community together, signaling power, saying what can't be said straight. Listen for the shuffle of feet and the call-and-response under everything; hear the old technologies of protection hiding in plain sight.

The canonical recording of ring shout in the Sea Islands—voices, sticks, feet, and ancestor time. You can hear the engine that later drives gospel, blues, and beyond.

Members of the Shouters explain what the shout is and isn't, how the circle moves, and why the practice persists. It's the tradition, narrated by its keepers.

A full concert in a formal hall that still sounds like praise-ground—call-and-response ringing through a national archive. The lesson here: our oldest forms keep their charge wherever they travel.

A journalist's walk-through of the shout's history and present—Watch Night, broomstick timekeeping, and coastal Georgia communities still keeping the circle. Useful context for ears new to the form.

Hurston's classic fieldwork names the practices and the language that later surface in blues lyrics and stage patter. Read to hear how conjure moved through everyday life and into song.

A tidy example of hoodoo talk walking straight into the blues—roots and remedies as lyrical vocabulary. Pair it with Hurston's essay to hear the echo.

The corridor's own description situates Gullah music as a throughline from African song to present practice. It frames why the sacred can live inside secular sound without losing itself.

Know something that belongs here?

If you've found performances, recordings, or scholarship about conjure music and the sacred-secular continuum, send them my way.

Suggest an addition